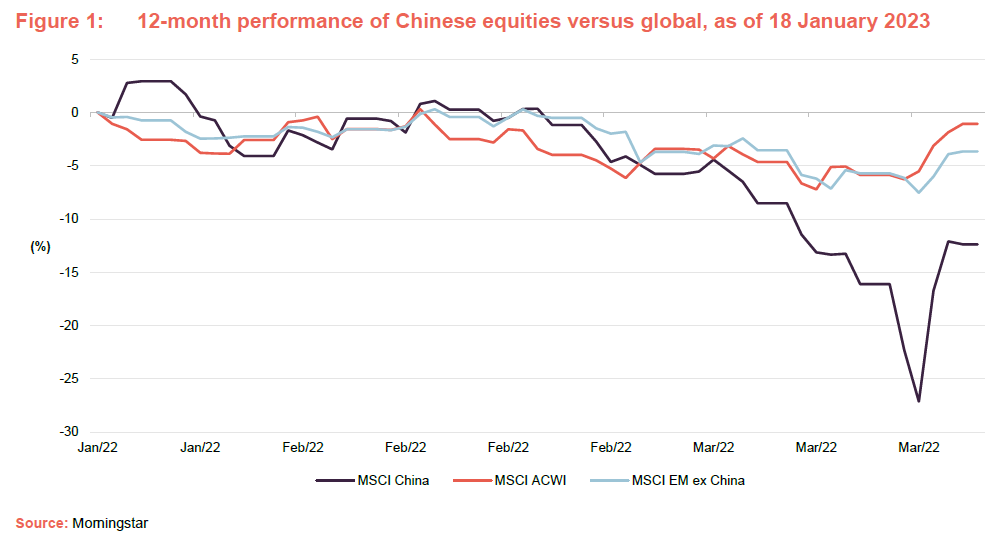

The lunar new year is upon us this weekend, bringing with it the year of the rabbit. According to the Chinese zodiac, the rabbit is associated with vigilance, quick wittedness, and ingenuity; and anyone born in 2023 will be born under the ‘water’ rabbit, and is expected to turn around the hardships of their youth. These are certainly poignant characteristics for Chinese investors, as the previous 12 months have been a painful roller coaster for the region’s equity markets. While the MSCI China has been able to generate a return comparable to both the MSCI ACWI and MSCI EM, as Figure 1 shows, it has been a far more painful journey, with the sector only recovering in the last quarter of 2022. In this article, we review the 12-month performance of the Greater China and Asia Pacific sector, to see if there are any strategies which have managed to produce noteworthy performance.

China sector overview

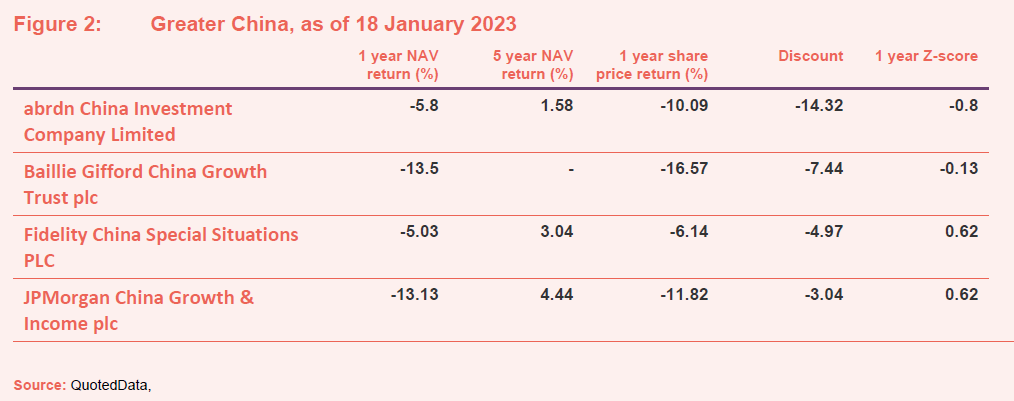

While the broader Chinese market has seen a rebound in performance, it has not been felt equally across the sector. The defining factor behind the bifurcation of the peer group’s performance has been the apparent biases to ‘new China’, high growth stocks across a range of market caps which, in theory, represent the future of China’s economy. But with the high valuations, biases to technology and consumer sectors, and overweights to high-growth small and mid-sized companies (which often demonstrate that ‘nimbleness’ that growth investors prize), it should be no surprise that such strategies have fallen foul of the post-inflation investor behaviour. This has seen highly valued companies across virtually all economic regions punished in favour of more economically sensitive, and conservatively valued companies. Given that none of the greater China trusts have been able to outperform the index over the last 12 months, the narrative is less about champion managers, but more about stylistic pitfalls.

One trust that we believe is worth noting is abrdn China (ACIC). While it isn’t the best performer, it has been able to broadly keep up with the MSCI China index. Something which is perhaps more impressive than it first appears, as it has a bias towards growth stocks. In contrast, Fidelity China Special Situations (FCSS) has more of a ‘value’ emphasis, given its managers’ focus on targeting undervalued companies, making its sector leading performance a more expected outcome.

One of the possible reasons behind ACIC’s performance, other than successful stock picking, has been its focus on quality, a common theme amongst many of the abrdn managed trusts. In theory, high-quality companies are less speculative, with longer track records, stronger balance sheets and more resilient earnings, thus allowing them to command higher valuations. ACIC’s sectoral allocations versus the MSCI China Index, the key benchmark for the region, are less pronounced than the rest of the peer group, making it less likely to fall awry of changing market sentiments. ACIC’s noteworthiness is compounded by its large, negative z-score, indicating its discount has widened much more than its peers over the period. Which may be paradoxical given its comparatively strong performance, making ACIC arguably an attractive way to capitalise on the China-recovery story (outlined below) without making a strong stylistic bet.

As an aside, for those investors who would like a fund with a decent slug of exposure to China but would prefer this to be part of a diversified exposure to the broader Asia-Pacific region, abrdn New Dawn (ABD) might warrant a further look. Like its sister trust ACIC, ABD combines an above average 12 month NAV return with the widest discount in the sector, and both trusts follow a similar quality-focused approach to investing. ABD is slightly underweight China versus its benchmark, but China still accounts for around a quarter of the fund. For investors looking to aggressively capture the high-growth potential of China’s economy, the two Ballie Gifford funds (Pacific Horizon and Baillie Gifford China Growth) might be more suitable options. Both strategies follow a high-growth approach to equity investing, with theoretically high upsides albeit coupled with higher volatilities. However, while China’s long-term growth story may lend itself to growth-focused strategies, neither Pacific Horizon or Baillie Gifford China offer the same discount opportunity as the abrdn trusts.

Made in China?

Even if one does agree with the notion that there are some China exposed strategies which are trading on attractive valuations compared to history, given the recent reversal of the region’s performance, the question remains whether or not there is any reason to buy these strategies today? Will a structural exposure to China be a tailwind for investors in the near term? China has certainly not been kind to investors over the last five years, as can be seen by Figure 3, a good chunk of which can be attributed to government policy. China’s equity markets have remained in limbo since the outbreak of COVID-19. An ineffective vaccine strategy, which remains a problem today, combined with economically-strangling lockdowns has meant that China has not benefited from the type of post-lockdown boom that the rest of the world saw.

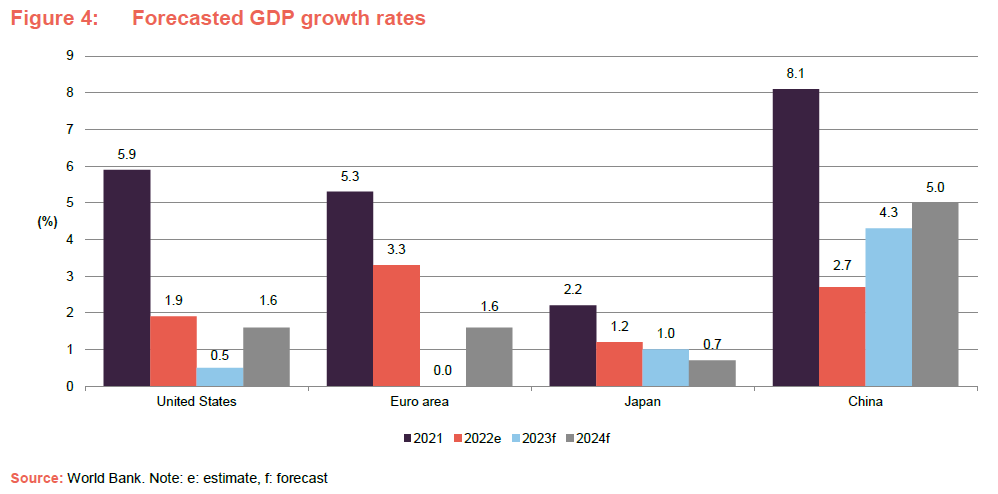

Yet it is because of this delayed re-opening that China may be worth buying. The simple fact is that global GDP growth is expected to decline over the coming years, especially in advanced economies as their post-COVID-19 bounce has given way to the painful realities of inflation. Yet China may offer investors a genuine alternative to global economic stagnation, as not only does it benefit from the imminent post-lockdown surge in economic activity, but it may also return to its structural growth trend that made it the engine for world GDP growth prior to 2019. There will also be new opportunities to be found in a maturing China, one which is moving away from being an export led economy to one driven by growth in its domestic consumption, a reflection of the growing wealth in China. With the idea of growing consumer strength being increasingly unlikely in the developed markets, China could be a useful source of growth.

Yet we must also acknowledge the major uncertainties surrounding China, which have seen little alleviation by the recent reopening, and how these could drag on both near-and-long term performance. The most immediate issue being China’s ability to tolerate the fallout of repealing their lock-down policies. Thanks to a lack-lustre vaccine program, and medical infrastructure which has been geared for containment rather than treatment, China will have to deal with the painful realities of surging COVID-19 death tolls, and an infected, and thus diminished, work force. Something which is only made more uncertain by opaque data coming out of China, with their authorities moving the goal posts on what can be classified as a COVID-19 related death.

There is also the political elephant in the room. Xi Jinping has now entered his unprecedented third term as President of the People’s Republic of China, having repealed the two-term limit on the position. While ardent China-bulls may applaud the continuity it could bring, it also means that his reach and power is effectively unchecked, something which has previously burned holders of Chinese equities. The highest profile market-related incident is arguably the Communist party’s blocking of the Ant IPO, which played a huge role in the downturn of Alibaba. Significant questions have been raised about the party’s influence over the company and its CEO and founder Jack Ma, who has now found refuge in Japan, and what the read-through might be for other successful entrepreneurs that become too influential for the government’s liking. Conventional wisdom is that we should expect the influence of the party on private business to continue to grow as Xi look to further solidify the party’s power, especially as recent COVID-19 protests have been a rare public discontent against the party’s policies.

Increased political influence may also do little to improve Chinese corporate governance, which can at times be described as ‘hostile’ to foreign shareholders, with ownership structures and laws designed to protect domestic investors over foreign. Yet even domestic investors have not been safe from Chinese corporate malpractice, with the collapse of Evergrande exposing widespread weaknesses in Chinas enormous property sector. And while likely a subject of another article, weakness in China’s property sector could end up being one of the major risks for the country’s long-term growth, given how important the sector has been in driving Chinese domestic economic activity. Of course, there remain the perennial issue of China’s ambitions around Taiwan and its territorial claims in the South China Sea, which could make the Ukrainian conflict seem like a playground scrap.

It may be good fortune that 2023 will be the year of the rabbit, as one may need some of that ingenuity to navigate the Chinese equity market. The combination of attractive discount in Chinese exposed strategies, with an economy that is bolstered by both a near-term post-lock boom and long-term structural growth drivers, may make the region an exciting alternative to the somewhat depressing growth prospects the western world is facing. Yet it is a double-edged sword, as risk factors in China are only evolving, with a myriad of often unquantifiable but none the less impactful factors, being clearly capable of making China’s risk/return profile unpalatable to some. While cautious rabbits may stay in their warren, the region’s advantages might just be sufficiently tempting to coax the more adventurous out of the nest.