This week I was fortunate to attend a seminar organised by Aberdeen Standard Investments (ASI) on inflation. The speakers included Iain Pyle, who is the manager of Shires Income, which we have written about a few times, and Nalaka de Silva, manager of Aberdeen Diversified Income & Growth, who we had on the weekly show not long ago.

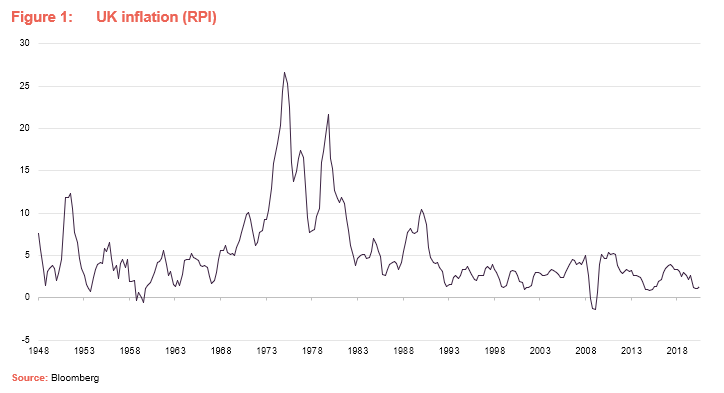

It is so long since high inflation was a global problem that many investors have no or only a patchy memory of it. A number of factors have combined to keep inflation low in recent years. Globalisation and increased automation have driven down manufacturing costs. The balance of the economy has shifted from labour intensive industries to capital intensive industries. As jobs, even those considered as skilled jobs have been eliminated by technology, the power of labour to demand wage increases has fallen. This is also a factor in increasing income inequality.

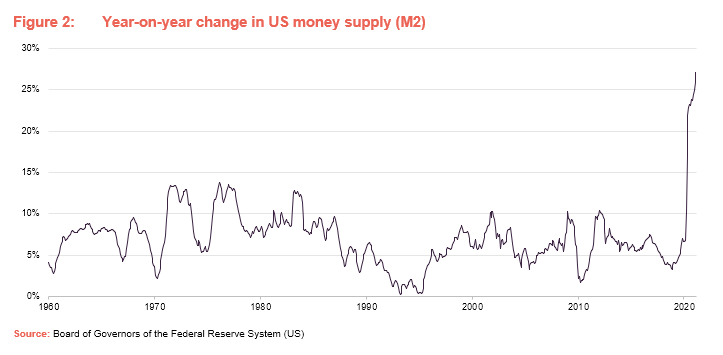

The policy response to shocks such as the financial crisis has been to lower short-term interest rates and keep longer-term rates low with quantitative easing (central banks buying bonds to push up their prices – which has the effect of driving down their yields). This policy allowed banks to rebuild their balance sheets and supported ever higher stock markets and house prices, but it didn’t put money in the pockets of most ordinary consumers so it did not cause inflation.

Government spending spree

However, this time perhaps it is different. Measures such as the vast stimulus plans in the US and furlough payments in the UK have stretched central banks’ balance sheets and handed money to consumers. COVID-lockdown restrictions have deterred many recipients from spending this, so far. Globalisation is faltering in the face of increased trade barriers. Oil prices and prices of many industrial metals are rising – see this week’s note on CQS Natural Resources Growth and Income for more information on this. Probably most importantly, as China’s recent record growth numbers suggest, we seem to be embarking on a global synchronised economic recovery.

Another argument is that overly indebted governments actually want inflation. They cannot recoup the money that they have spent since COVID-19 hit through taxation, at least not without tipping their economies into a prolonged slump. Inflation erodes the value of that debt, however.

Free to splurge

Since we got the good news on vaccines last November, the mood has shifted. Travel companies, retailers, pub chains and the like are looking forward to us splurging the money we have saved as we emerge from lockdown. The markets have started to worry that this will translate into higher inflation. The principal effect has been that longer-term interest rates have started to climb. The logic is that, if more of my return is likely to be lost to inflation, I want a higher return. The numbers look tiny – US 10-year treasuries offered a yield of 0.88% on 31 October 2020, last night that yield was 1.56% – but the effect on markets is significant.

Rising long-term rates are behind the profit-taking on growth stocks – big falls in the likes of Scottish Mortgage, for example. They also decrease the attraction of funds whose principal attraction is yield rather than capital growth. Meaningful inflation could pull the rug out from all sorts of investments.

Modest inflation is priced in

Amit Moudgil, a fixed income investment specialist at ASI, says the market is pricing in inflation in the US of about 2.4% in five years’ time. Expectations for inflation in the EU are lower, where there has been less stimulus and the vaccination programme is in a mess, but higher in the UK.

The overall view at ASI seems to be that inflation may tick up a little but is not likely to become a real problem in most markets. They think that the factors that have kept the lid on inflation in recent decades will continue to constrain price rises. Although Nalaka did highlight that inflation in services is often much higher than inflation in goods. The ASI speakers noted that there have been some inflows of cash into inflation-protected securities such as US TIPS and index-linked bonds. They are expecting that long-term bond yields will fall back again (and this seems to have been happening this week).

If the ASI team is wrong, and inflation does start to build, we might expect to see a sell-off in markets. In the long-term equities would still be the best place to be as companies can protect their profits by hiking prices – companies with pricing power should be prized, therefore. Bonds and cash would be less attractive. If the ASI team is right, where will all the governments’ extra cash end up? If the past is a guide, probably in ever rising asset prices.

At the moment, the picture is clouded and we may see some continued volatility in markets as different indicators point to rising or falling inflation. I do expect this to continue to be a focus for investors for some time yet.

You might also want to read the QD view from 5 March.